[ad_1]

Rachel Gordin Barnett and Lyssa Kligman Harvey have been friends for decades. Both Jewish natives of South Carolina, their mothers knew each other growing up — but they recently stumbled upon an even older connection.

“My grandmother actually, her papers when she became an American were signed by Lyssa’s grandfather. We didn’t know that,” Barnett told The Times of Israel in a recent joint Zoom interview from South Carolina. “We didn’t know that, and we’re dear friends. So this is how it goes in South Carolina — small Jewish community.”

The unique and close-knit Jewish community of South Carolina — and its culinary traditions — are the focus of a new book, “Kugels and Collards: Stories of Food, Family, and Tradition in Jewish South Carolina,” out this week from the University of South Carolina Press.

The book, part cookbook and part exploration of South Carolina’s Jewish history, is a collection of stories and essays about food experiences related to the Palmetto State’s Jewish community, dotted with old family recipes and a handful of newer culinary creations.

“What I like to say is: I’m Jewish, and I’m Southern, and food is my love language,” said Harvey. “Because of our history, and because storytelling is so important for all religions and traditions, I feel like Rachel and I are giving the South and the Jewish Southerners something long-lasting, a little bit of a legacy.”

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

The book grew out of a blog by the same name launched by the pair in 2017 under the aegis of the Historic Columbia nonprofit, which sought to explore memories and stories of Southern Jewish foodways with their connections to the local culinary scene and their ancestors’ traditions.

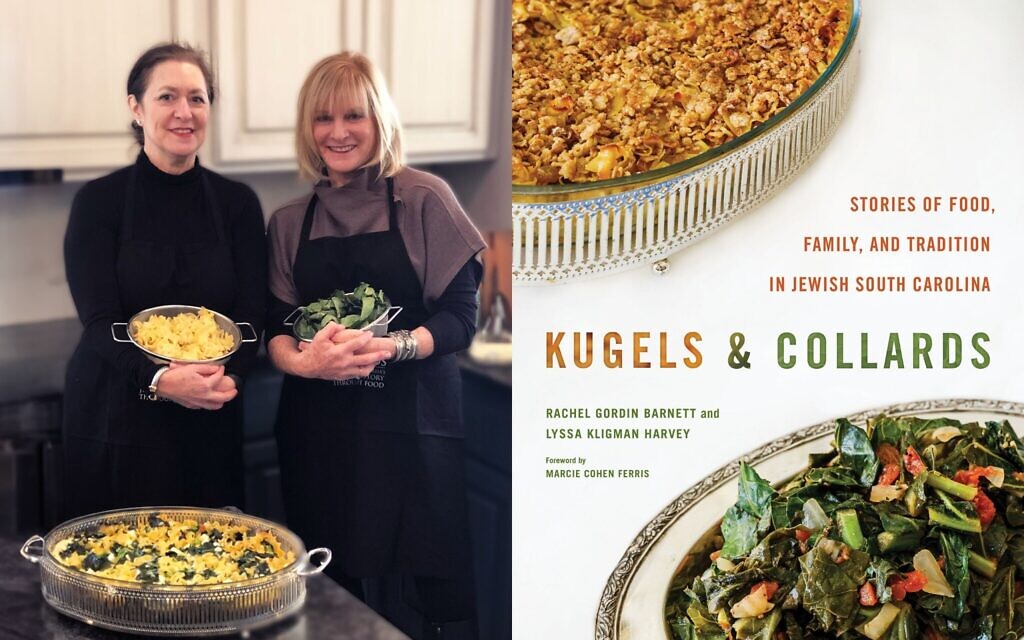

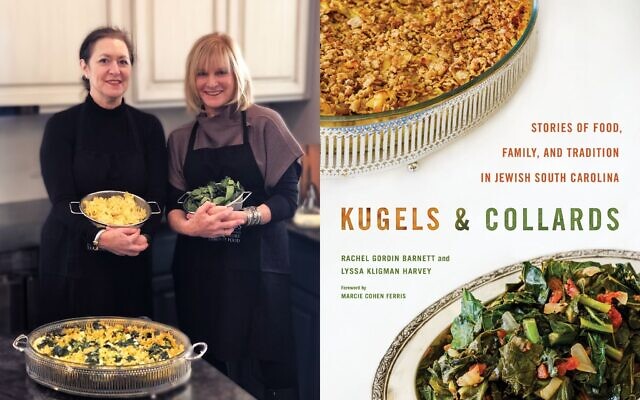

Rachel Gordin Barnett (left) and Lyssa Kligman Harvey alongside their new book, ‘Kugels and Collards.’ (Courtesy)

In a range of essays gathered from South Carolinians past and present, “Kugels and Collards” tells the stories of a wide swath of Jewish immigrants to the state, from Sephardic Jews who arrived in the late 1600s to an influx of Eastern European Jews at the turn of the 20th century, and even those who put down roots in the state in the past 20 years. Barnett and Harvey solicited and compiled stories and recipes from friends, family members and strangers to paint a picture of the community, its traditions and its history.

“Truly, we ate like our Southern neighbors, but with a few notable exceptions — Granny and Mother did not cook with bacon grease or store it in a special little can on top of the stove,” wrote Rhetta Aronson Mendelsohn and Carol Aronson Kelly about growing up in Orangeburg, South Carolina, in the 1950s and 1960s. “Our menus included things our neighbors knew nothing about — chopped liver, herring, blintzes, bagels, lox, brisket, potato and noodle kugel, matzo balls, matzo brei, and more. So, when we went to the beach every summer, we took along fried chicken, barbeque, and deviled eggs as well as chopped liver, herring, and brisket.”

The book paints a portrait of a colorful collection of figures, both Jewish and non-Jewish, from Max Dickman, the longtime “latke king” of Columbia, South Carolina, who was always in the kitchen at the Tree of Life Temple Hanukkah parties; to Larisa Gershkorich Aginskaya, a Ukrainian Jew who moved to South Carolina in 1979 after years living in Uman where she catered kosher food for visiting Hasidim, and who later become the kitchen director of the Beth Shalom Synagogue; and Florida Mae Boyd, a Black housekeeper turned caterer once called the “best Jewish chef in Columbia.”

Most of the recipes in the cookbook are traditional Jewish Ashkenazi fare, from matzah ball soup to kishke, gefilte fish, noodle kugel and more. There are also some lightly adapted Southern staples, including fried green tomatoes, Hoppin’ John, okra gumbo and fried chicken — plus a few modern takes on the intersection of cuisines, including recipes for grits and lox casserole and savory Southern kugel with collards.

Lila Lash in front of Lash’s kosher market in Charleston, South Carolina in 1992. (Courtesy Jewish Heritage Collection/ College of Charleston Libraries)

“The old Southern Jewish table was not a mashup,” said Barnett. “It was more of a bringing together of all of these foods — the Southern, the cultural foods, the collards and okra and tomatoes and corn and rice, along with the brisket and kugels and matzah ball soup.”

The authors also sought to pay tribute to the influence that Black domestic workers in Jewish homes had on the development and preservation of their cuisine, citing their contributions and honoring their role.

“It’s really one of the main underlying themes, is that not only do we live in the South and eat our foods that surround us, but the African American culture has brought that to us, and we are so grateful and honored to include that,” said Harvey.

Barnett wrote in the book about Ethel Glover, an African-American housekeeper who worked for her grandmother, Sarah, in the 1930s in Summerton, South Carolina.

“Sarah taught Ethel traditional Jewish recipes and kosher rules, and, in a reciprocal fashion, Ethel brought African American and Southern dishes such as fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, rice, squash casserole, okra and tomatoes, collards, and many vegetable recipes to the Gordin home,” she wrote. “Their recipes were never written but were told and passed down for generations.”

While at times the book reads as a love letter to a community and time gone by, both Barnett and Harvey are adamant that though the South Carolina Jewish community is evolving, it’s still going strong.

“I would tell you that it’s changing,” said Barnett, noting that the earlier wave of immigrants were merchants many of whose children obtained college degrees and mostly moved elsewhere. “Charleston’s Jewish community is growing, people are moving in. It’s a changing look… we have a university which brings people in.”

The co-authors said they hope the book and its stories can inspire people to explore their own culinary and family histories.

“Through sensory experiences of food, the smell and the visual and the taste, it brings about very emotional kind of visceral memories,” said Harvey. “And then one memory leads to another, and before you know it, you’re not really talking about food, but you’re talking about people and you’re talking about funny things… so I just love where food takes us. I hope that we all savor the story.”

Recipe: Hyman’s Seafood Salmon and Grits

This dish is on the menu at the Jewish-owned Hyman’s Seafood in Charleston, South Carolina as an alternative to shrimp and grits for kosher customers.

Ingredients:

Salmon:

4 fresh salmon filets

1 teaspoon kosher salt

Cajun seasoning (optional)

1 tablespoon olive oil

Grits:

1 cup locally milled grits

2 teaspoons salt

2 cups of water or milk

2 tablespoons butter

1 beaten egg yolk

Any fine-grained breading or cornmeal and flour

White sauce:

½ cup chicken broth (to make the recipe kosher, substitute vegetable broth)

½ cup milk

½ cup heavy cream

1 stick of butter

2 teaspoons minced garlic salt and pepper

1½ cups grated Parmesan cheese

Paprika

Directions:

To make the salmon:

Sprinkle the salmon filets with kosher salt (and Cajun seasoning, if using), and drizzle the olive oil onto the filets. Broil or bake the filets in a conventional oven for 8–10 minutes. Be careful not to overcook the salmon.

To make the grits:

Put 1 cup of grits into 2 cups salted boiling water until the water returns to a boil. Turn down to a simmer, add butter, and cook slowly, stirring constantly and adding water so that it doesn’t burn.

To make a grit cake:

Prepare the grits and put the grits in a greased sheet pan overnight. Once it has hardened, you can cut out round cakes. Brush the beaten egg yolks over both sides of the grit cake. Dip into the breading. Fry the grit cake in a cast iron skillet.

To make the white sauce:

Add the broth, milk, cream, and butter to a large saucepan. Simmer over low heat for 2 minutes. Whisk in the garlic, Cajun seasoning, salt, and pepper for 1 minute. Whisk in the parmesan cheese until melted.

Put the salmon over grits or grit cake. Pour the sauce over the salmon. Shake a little Cajun seasoning or paprika on top for color.

Recipe reprinted with permission from “Kugels & Collards: Stories of Food, Family and Tradition in Jewish South Carolina,” by Rachel Gordin Barnett and Lyssa Kligman Harvey, University of South Carolina Press.

[ad_2]

Source link