[ad_1]

Packing for six children and getting them out the door is the straightforward part of Yehuda Fua’s preparations whenever his family wants to visit one of the natural springs that draw thousands of Israelis each summer.

Like most Haredim — strictly observant Jews who make up roughly 17% of Israel’s Jewish population — Fua’s observance prevents him, his wife and older children from entering the water in the company of members of the opposite sex.

But unlike Israel’s 16-odd sex-segregated beaches, none of the dozens of springs maintained by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority make accommodations for that modesty-based requirement. So Haredim like Fua, a 38-year-old resident of Afula and right-wing activist, either try to come early enough to beat the nonobservant visitors, or give up on the experience altogether.

“Most times we don’t bother. It’s effectively off-limits for us,” Fua, the co-founder of B’Tsalmo, a conservative human rights group, told The Times of Israel this week.

To address this, Environment Protection Minister Idit Silman, a religious lawmaker from Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party, last week announced that two nature reserves near Jerusalem — Einot Tzukim and Ein Haniya — would stay open after hours for segregated swimming this month.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

But her plan was suspended indefinitely for unspecified reasons by the Attorney General’s office, which is reportedly examining it as the summer holiday nears its end.

To some, the move by Silman was an act of religious encroachment on a largely secular pastime at the height of a polarizing fight between traditionalists and secularists about religion-state relations, and came amid the government’s divisive push to overhaul the judicial system. To others, it’s an overdue correction whose suspension by bureaucrats is proof that the overhaul is necessary to ensure representation for a conservative public, who some believe has been sidelined by an unelected and largely liberal elite judiciary.

Silman, in an interview with The Times of Israel, declined to discuss the broader aspects of her plan’s fallout, describing it merely as a legal error by Deputy Attorney General Avital Sompolinsky.

“I’m not going into these matters at the moment,” Silman said when asked about whether the affair is part of the religion-and-state debate and the controversy around the judicial overhaul, which seeks to weaken the judiciary and thus increase the power of elected officials.

Water gathers into a pool at Einot Tzukim in the Judean Desert on January 3, 2017. (Melanie Lidman/Times of Israel)

Silman said that the plan, which was supposed to begin last week, got suspended after legal advisers at the Nature and Parks Authority consulted the deputy attorney general’s office. Queried about the suspension, Avishag Ifergan, a spokesman for the Justice Ministry, under which Sompolinsky works, replied in an email: “The issue is still being looked into. We will not be elaborating on it at this stage.”

According to Silman, Sompolinsky suspended the plan based on the actions of her predecessor, Dina Zilber, who in 2020 torpedoed a previous attempt to institute gender-segregated swimming at a nature reserve, saying it undermined principles of equality upheld by the Supreme Court.

“There were a few problems in the 2020 plan,” Silman said. “Mainly, the segregated hours came at the expense of the non-segregated ones. We addressed those problems by adding extra opening hours for both segregated and non-segregated swimming at times that wouldn’t disturb wildlife,” she said.

Deputy Attorney General Avital Sompolinsky attends a Constitution, Law and Justice Committee meeting at the Knesset, January 19, 2023.(Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

The suspension is “not legitimate because it’s an interference without proper cause,” Silman said. On Wednesday, her office sent a letter to Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara and Sompolinsky protesting the delay in authorizing and reviewing the segregated swimming pilot program.

Overall, Silman told The Times of Israel, “I trust the professional establishment. I hope no one at the Attorney General’s Office is trying to perpetuate the unconscionable and hurtful exclusion of a huge swath of the population – which includes devout Muslims in addition to Jews – from access to our shared natural and water resources.”

Moriya Litvak, the director of Yehudit, a conservative women’s rights organization, isn’t buying the legal arguments. She describes the plan’s suspension as proof that the judiciary is adopting a liberal approach that views the concealment of feminine features as a result of patriarchal oppression. “This is about a radical feminist view against modesty, imposed by a left-leaning attorney general’s office in 100% of the nature reserves,” Litvak said.

Shai Glick, left, and Yehuda Fua, the heads of the right-wing advocacy group B’Tsalmo, demonstrate in favor of the judicial overhaul in Jerusalem, Israel in February 2023. The sign reads: “End the tyranny of the minority.” (Courtesy of B’Tsalmo)

To Litvak, “this shows the centrality and necessity of the judicial overhaul. Instead of assisting elected officials, legal advisers and bureaucrats hamper them. When the overhaul happens, we’ll enjoy, among other things, equal access to natural resources too,” Litvak said.

Opponents of sex-segregated swimming at nature reserves say that the push to make it happen is part of a broader drive to turn Israel into a theocracy – a prospect that they fear will be facilitated by the judicial overhaul that the Likud party and its five religious coalition partners are leading.

The Nature and Parks Authority is “pressured by religious parties bent on oppressing women and limiting our rights in the public space,” Karni Ben Yehuda, a graphic designer and feminist activist, wrote in a petition against segregated swimming in nature reserves. “It’s a dangerous precedent and if it happens, more public entities might discriminate legally against women,” said the petition, which has received more than 125,000 signatures.

A Byzantine-era pool discovered at the site of Ein Haniya, near Jerusalem, and revealed to the public on Wednesday, January 31, 2018. (Assaf Peretz/Israel Antiquities Authority)

Or Kashti, a reporter for Haaretz, wrote in an op-ed published Sunday: “Nothing stops Silman and her comrades in the regime coup,” a term for the judicial overhaul that is favored by its opponents. “She’s determined to despise the law, and continue to undermine in yet another sphere of life the principle of equality while uttering sweet-sounding rhetoric about ‘consideration’ and ‘sensitivity’ and multiculturalism.”

Concerns about jeopardizing women’s rights “are being confirmed, whether by the expansion of rabbinical courts or the normalization of segregated concerts, leisurely activities and in academia,” Kashti wrote, referencing previous controversies around sex segregation.

One recent controversy was a bill proposing a requirement for segregated facilities at nature parks with water sources submitted in January by Moshe Gafni, a leader of United Torah Judaism, a Haredi party and one of Likud’s coalition partners. The bill, which is a resubmission from the previous Knesset, seems to be dead in the water: It has not advanced toward a preliminary reading.

Men and boys bathe at a gender-segregated beach in Herzliya, Israel in July 2012. (Wikimedia Commons)

“People from overseas would think they’d landed in Iran by mistake,” tour guide Amnon Gofer told Radio FM103 in January about the bill. Besides, he added, Haredi people don’t typically go out to nature. “Let’s be real: Yeshiva students go home [on holidays], they’re not out in nature all the time.”

Yisrael Shapira, a well-known tour guide for Haredim, chuckled at this assertion. “Tell that to the dozens of tourism businesses predicated on Haredi visitors,” he told The Times of Israel. Haredi hikers mostly visit during three months a year, and especially in summer, when yeshiva students are on break, Shapira said. “But when they come, they come en masse. This only facilitates setting up segregated swimming during those three months alone,” he argued.

Some springs, such as Gan Hashlosha (Sahne) near Afula, a cherished park with clear, turquoise-tinted waters that have a constant temperature of about 28°C (82.4°F), have multiple pools that facilitate operations for segregated bathers and non-segregated ones simultaneously. Others, like the Hexagonal Pool in the Golan Heights, a deep and cool body of water named for the remarkable volcanic rock formations that adorn its edges, have a space requiring separate times.

A waterfall spills into the Hexagonal Stream in the Golan Heights. (Courtesy of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

Hiking with children in the absence of water is difficult in Israel, an arid country where temperatures can easily reach 39°C (102°F) in the shade. This reality has led to disputes over access to water, which often become a proxy of broader societal grievances, such as the Ashkenazi-Sephardic divide that was on display in a fight over the Asi Stream, or Nachal Amal.

Following a decade of litigation that reached the Supreme Court, an agreement was reached this year that allows visitors, mostly from the poorer and largely Sephardic city of Beit She’an, limited access to the Asi Stream through Nir David, the affluent and heavily Ashkenazi kibbutz that for decades had illegally barred non-members from entering the place.

Litvak, the religiously devout feminist, favors nature outings to the few springs that dot the West Bank that have not yet been declared parks. The local Jewish population, which has more devout people than the national average, “works out its own, grassroots timeshare programs. People just negotiate it on the ground, giving women and men equal time in the water,” she said.

The Amal, or Asi Stream flowing through Kibbutz Nir David in northern Israel, August 9, 2020. (Menachem Lederman/Flash90)

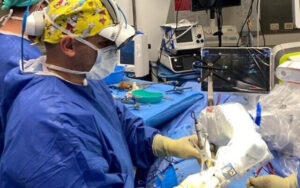

As an experienced tour guide, Shapira, a 33-year-old father of four from Modiin Ilit, brings Haredi groups to springs when they are almost sure to be deserted. “So we come at night. We come very early. Sometimes even that doesn’t help and we feel humiliated and marginalized,” he said.

Some secular people protesting sex segregation fear feeling the same way.

“It will begin with natural springs, continue to segregated walking lanes and end with allotting men the majority of space and time at women’s expense,” Uri Misgav, a columnist for Haaretz, wrote in 2021 about an earlier, unsuccessful plan to institute segregated swimming at nature reserves.

“Strategically, the Haredim will consume us, there’s no alternative. It’s not ‘antisemitism,’ it’s an honest analysis of social, economic and demographic trends,” Misgav wrote.

But if that’s true, then that’s only more reason to be generous to Haredim when they’re the minority, Fua, the father of six from Afula, argued. “If you fear we’ll overrun you when we’re the majority, why would you want to oppress us and humiliate us now, by depriving us of just a few hours a week at a nature reserve?” Fua demanded.

[ad_2]

Source link